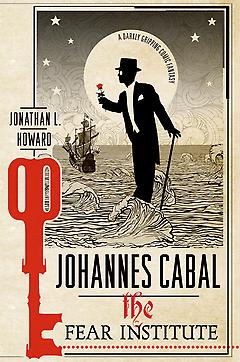

I’m not sure at what point I decided to set the third Johannes Cabal novel—Johannes Cabal: The Fear Institute—in the Dreamlands of H.P.Lovecraft, but I do know that once I’d thought of it, I was very engaged by the idea. The previous novels had followed different… I hesitate to say genres or tropes, but shall we say styles of story—Johannes Cabal the Necromancer being a picaresque tale of the “evil carnival” sort, but told from the point of view of the poor schmuck who is in charge of such an enterprise, and Johannes Cabal the Detective being a golden age locked room murder seen through the prism of a faux Victorian/Edwardian setting with a few “steampunk” trappings.

I wanted the third book to have some swashbuckling and high fantasy, but Cabal’s world was not a perfect fit for such a story. Happily, there was one impinging upon it, and, I like to think, every other fictional world regardless of genre—the Dreamlands.

The genesis of the Dreamlands is well known, so I won’t spend long retelling the tale. In the earlier part of his career, Lovecraft was strongly influenced by the fantasies of Lord Dunsany. I’ve read Dunsany and didn’t enjoy the experience, but Lovecraft became fascinated by these strange fables and they inspired him to have a go at something similar himself. His, I’m relieved to say, are much more readable. While it’s generally accepted that Lovecraft was no great stylist, he did have a prodigious and ingenious imagination. He suffers along with the likes of Edgar Rice Burroughs—his work often seems predictable now purely because his ideas have been stolen and recycled so many times in the decades since.

The Dreamlands, then, are (is?) a world influenced by dreamers not only from Earth, but other worlds and dimensions. Its reality is reasonably solid, but prone to shifts in perception. It is very ancient, and resistant to wholesale change, not least because many of the most powerful dreams that shape it belong to entities that sleep a very long time and are not prone to the mayfly vexations of humanity.

In character, they are Scherherazadian, albeit combined with the high romance of the early 20th Century pulps. There are enchanted woods, mighty castles, besilked and bejeweled merchants crisscross seas dense with pirates and monsters, and both turbans and zebras are more common than you might expect in your dreams. Everything is bigger, richer, more glorious, and more dangerous than Earth. Lovecraft being Lovecraft, however, he couldn’t leave it at that. The Dreamlands are also a crossroads for some of the nastiest extraterrestrial and extradimensional entities ever to trouble reality. They don’t just clump into the place as if at the behest of Michael Bay, though (possibly an extradimesional entity himself), but weave plans and influence matters with greater or lesser degrees of subtlety. The Dreamlands are also the retirement home of several gods or, at least, godlike creatures, who just want to be left alone and tend to overreact if disturbed.

This, then, was my setting.

I promptly set upon breaking it.

I don’t want to go into too many details, spoilers and all that, but if you look inside the book you will find a map of the central bit of the Dreamlands where the novel’s action predominantly takes place. If you’ve ever seen any other maps of them—and there some beautifully drawn ones out there—you will likely notice that I have taken a few liberties with the locations of some of the land masses and features. In the afterword, I say that’s how I dreamt it. That may sound fatuous (largely because it is), but nor is it entirely untrue.

My research consisted of pulling together my collection of Lovecraftianalia (which is too lovely not to be a word, so now it is) which included two similar but not identical maps of the Dreamlands, and rereading Lovecraft’s Dreamland stories, with special emphasis on The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath (a novella, but I shall dignify it with italics nonetheless), “The Doom That Came to Sarnath,” and “The Cats of Ulthar.”

Thus equipped, I embarked upon the expedition. Sorry. “Novel.” I meant “novel.”

As it progressed, I noticed an unusual tendency. Where I needed a specific fact, I was quite happy to pick up the relevant book and check on it. When it came to the geography, however, I found myself strangely reluctant to do so. The maps were right there, by me. I could just look at them, should I so choose. I chose not to. All I was running on was a brief glance at them when I first collected my materials and, for some reason, I was fine with that. This was symptomatic of the writing of the book as a whole. It flowed organically from my imagination to the page and did not care to be moderated by what somebody else reckoned along the way. I appreciate that this may sound breathtakingly arrogant—to take Lovecraft’s toys and play merry hob with them—but it’s actually very much in the spirit of what other writers have done and, even if I have sometimes disagreed with directions they have taken, at least I now understand the process that overtook them and allowed them to do so.

In essence, I think all of us have a Schrödinger’s Dreamlands in our heads, and expressing it through prose, or poetry, or art collapses its waveform and, for better or for worse, there it is. I shifted a major island and a few features. I created a new, small island that is everywhere and nowhere. That’s my Dreamlands. It’s different from everyone else’s, and that is right and proper. I’m comfortable with it and, should you ever feel moved to create something set in the Dreamlands yourself, I hope and trust that you are comfortable with yours too.

A final note. After I submitted the manuscript to my editor at Headline, she wrote back with her notes on it and included one unexpected anecdote. She told me she had been reading it one evening, completing a chapter in which Cabal and the Fear Society suffer a macabre encounter with some creatures of the Dreamlands, creatures of my own invention (because, obviously, the Dreamlands doesn’t have quite enough macabre things in it already). After she went to bed, she had a nightmare in which these horrors appeared. While she didn’t much enjoy the experience at the time, she was happy about it in retrospect; the book must be doing something right if elements were lodging in the subconscious. For my part, I’m wondering if I haven’t inadvertently introduced something new and horrible into the collective consciousness.

Ah, well. Sweet dreams.

Jonathan L Howard is a game designer, scriptwriter, and a veteran of the computer games industry since the early 1990s, with titles such as the Broken Sword series to his credit. After publishing two short stories featuring Johannes Cabal, Johannes Cabal the Necromancer was published in 2009. This was followed by Johannes Cabal the Detective, and Johannes Cabal: The Fear Institute, and most recently, his original Tor.com story “The Death of Me.”